Sunday 30th June 1940, just nine months after the outbreak of World War II, the last family left their homes on Mynydd Epynt in what is described as the death of an entire community. Farming Wales reporter, Clare Williams, writes about the heartbreak and memories that live on today, 80 years after the Epynt clearance.

Following the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, the school on Mynydd Epynt was visited by an Army officer, causing concern amongst some of the residents that the Army might want to use some areas of grazing land.

The following January, when the military returned, real worry began to set in. The Epynt community carried on as usual until March 2nd, following the annual St David’s Day celebrations at Capel y Babell the previous day, when eviction letters started arriving.

The 219 inhabitants of the 54 farms within the Epynt community were given just three months to pack up and find somewhere else to live. To leave their homes and the community where their fathers and grandfathers before them had cared for the land.

The predominantly Welsh speaking community believed they had forced the MoD to reconsider, however in April that same year, after Hitler’s blitz of Norway, London had no interest in the community’s argument any longer and they were given until the end of June, a month longer than the original eviction date, to leave the mountain.

The following two months saw the grief-stricken community race to find somewhere else to live, somewhere else to raise their families and rear their stock. There weren’t many local options available, and with 54 farming families needing to relocate, many were forced to move out of the area.

Elwyn Davies, who lives in Merthyr Cynog, was 10 at the time and recalls how his grandmother was forced to move, eventually finding a new home in Carmarthenshire.

He said: “It was a very sombre time. It was war time, and there weren’t many options locally. My Mamgu, who lived at Gwybedog, moved to Pumsaint. It would have been 20 miles away as the crow flies. Just a week after she left, they flattened her house. They flattened everything.

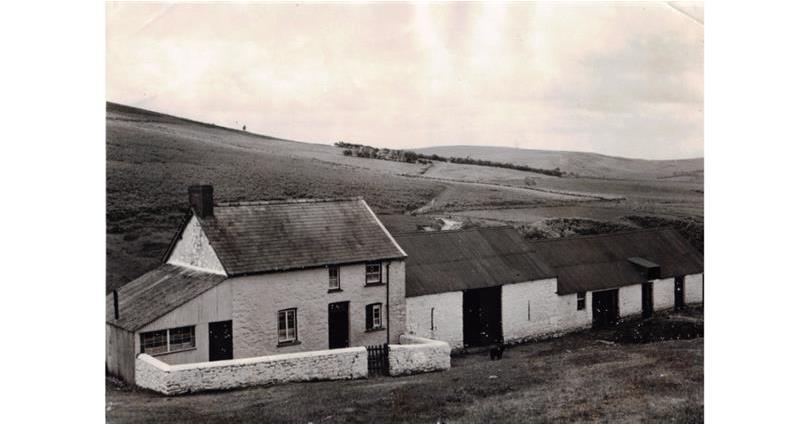

Gwybedog

"She’d gone from living just over the hill to a full day’s travel away. I remember once, my father and I went to visit. We caught a bus from Brecon to Llanwrda and started the walk from there, which would have been around 10 miles. But we managed to thumb a lift on the back of a timber lorry which took us another six or seven miles. I vividly remember my father holding on to me tightly as we weaved back and forth over the Dulais. No doubt it wouldn’t have been very quick by today’s standards, but it was quite an adventure for a 10-year-old boy. It dropped us off just before Pumsaint and we had to walk the rest of the way to Coed-y-Gof.”

It wasn’t all bad memories for Elwyn though, who is the father of NFU Cymru President, John Davies. He recalls: “As a child, it all seemed very exciting. I went to school in Merthyr Cynog and we spent ages watching the Army trying to get the big lorries up over the hill. We’d never seen anything like it before.

"We could hear the guns from school as well. One of the Army officers in charge of things lived in the vicarage and we used to try and run down the road to hitch a lift to school. We were always reminded of the seriousness of it all though, and how hard it was on some people.”

At the time, locals were told it was part of the war effort, and some even believed that the arrangement was temporary and that they would be able to return after the war. Sadly, this was not the case. In June 1940 the school and chapel closed, the Army started removing hedges, and on Monday 1st July 1940, heavy artillery firing began.

One resident, Thomas Morgan, who had managed to find a new home just south of the range, would regularly walk back to his old house to light a fire, to keep the house temperature ready for the family’s return. One day, having negotiated his way up the Ysgir Fechan Valley, he reached Glandwr and was stopped in his tracks, as the house he had grown up in had been reduced to a pile of stone and rubble. A military officer approached him and said ‘We’ve blown up the farmhouse. You won’t need to come here anymore’.

Ceinwen Davies with the remains of Gwybedog

Lee Waters, Labour MS for Llanelli, remembers the sense of loss his Dadcu had, having left the Epynt to move to Llwyn Wennol in Gwynfe during the clearance. He said: “My grandfather, Ivor Morgan, farmed Neuadd Llwyd on the Epynt, first with his grandparents, then his father. He was 32 when they were forced to relocate.

“He’d moved to the farm following the death of his mother when he was eight and said that they were just getting the flock up to the right size when they were forced to move. There wasn’t any anger at the time because they thought they would be returning to the farms, and I never sensed any bitterness, but there was definitely a sense of lament.

“The dislocation felt from the stubbing out of a whole community was a huge sacrifice made in the name of the war effort. My Dadcu certainly felt a deep connection with the land that he farmed all the way through his formative years, and never lost his affinity for it. I have a precious memory of returning with him in his mid-80s to the chapel in Merthyr Cynog where his parents are buried, for him to place a headstone for his father. Right into his final years, the Epynt and its people were alive in his mind.”

Pic by PRW Photography: The Army training on Mynydd Epynt

Today, the MoD still own the 30,000 acres of Mynydd Epynt, now known as the Sennybridge Training Area. There’s a mock village that was built in the 1980s in the Cilieni Valley, which is based on a typical small German village. It is known as a ‘ghost village’ and is still used today by soldiers training for FIBUA or ‘Fighting in Built up Areas’. A timetable for live firing is published every month by the MoD.

Almost all of the original buildings, including the farmhouses, have been destroyed apart from the pub, The Drovers Arms Inn, the only nod to the families who lived there 80 years ago.

The Drovers Arms Inn

It wasn’t just the loss of life that was uprooted but also the Welsh language. Families living in the area were dispersed into more Anglicised areas of Brecon, and the boundaries of Welsh speaking Wales were pushed further west, into Carmarthenshire.

Ben Lake, Plaid Cymru MP for Ceredigion, who also has a family connection to Mynydd Epynt, said: “The takeover of the Epynt 80 years ago is a significant - but often overlooked - chapter in the history of Wales. An entire community was displaced, and families had to vacate farms that had been farmed by their ancestors for generations.

“As a grandson of Beryl Lake, the last baby to be born on the Epynt, I am so glad that the events of 80 years ago are being remembered, and I hope that more people will come to learn of how a rural community was lost to the area, but also how the Epynt is an important part of Wales’ agricultural heritage. My grandmother named her home in Llanddewi Brefi ‘Beili Richard’, after the farm that she was born on, and so as a family we are fortunate that a part of the Epynt will always stay with us.”

Family connections with the Epynt are well known within the Brecon and Radnorshire community. The family of NFU Cymru County Adviser, Stella Owen, originated from Cefnioli farm and her great grandfather, David, moved to Rhiwgoch, between Pontfaen and Llanfihangel Nant Bran. The rest of the Owen family relocated to Sarncwrtau, Llandulas in Tirabad.

Stella said: “David married Margaret Lewis of Abercriban, and they had three sons, one of which was my grandfather Gwilym, who stayed at Rhiwgoch Farm and raised four children with my nan. This remains in our family today. There are also pictures of my great grandmother, who went to school on Epynt, in the book ‘Epynt Without People’ which has always sat on the dresser at home. My great grandmother married into the Richards family and she was known as ‘Gran Tirfelin’ to us children. She is buried with her family at Sardis Chapel which sits at the foothills of Epynt. I go back to put flowers on the graves, and it is after ‘Gran Tirfelin’ that our daughter Lexi’s middle name of Adela follows.”

The fields being ploughed at Gwybedog around1940

NFU Cymru Environment and Land Use Adviser, Rachel Lewis-Davies, also has a strong connection with the Epynt. Her grandfather, Evan Rees Lewis, who lived at Abercriban farm with his father and three brothers, moved with his youngest brother to Llandeviron, Paincastle. In 2002, Rachel and her family returned to farm Epynt when they managed to secure the tenancy of Spite Inn, Tirabad.

Rachel said: “The story of Epynt is one that we must continue to tell and learn from. What happened here 80 years ago has relevance to Welsh farming and rural communities today, with concerns over land use change from farming to make way for large scale afforestation or rewilding, to address the big challenges of our time. Epynt is a reminder that communities have value and they are an important part of Welsh rural life.”